History & Epidemiology

A bifurcation lesion is a common health issue that occurs when a coronary artery narrows, adjacent to or involving a significant side branch.1 These are caused by plaque deposits comprised of fat. Bifurcations are a type of coronary artery disease, a serious medical condition that ranks as the leading cause of death in the US.2

Coronary bifurcation lesions can be either simple or complex, accounting for approximately 20% of all percutaneous coronary interventions.3 They represent a challenge to medical professionals since this condition is known for its cardiac side effects and lower interventional success rates. Although a number of treatment options have been used, provisional side branch stenting is the most commonly used treatment and the intervention associated with the lowest risk of failure.

Patients with bifurcation lesions will need to be monitored carefully as they also have an increased risk of developing atherosclerosis.4

Bifurcation Lesion Presentation & Diagnosis

If a patient presents with the following symptoms, they should undergo testing for coronary artery disease, which may include bifurcation lesions5:

- Discomfort or pain in the chest area

- Pain in the shoulder or arms

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea

- Cold sweats

- Lightheadedness

If patients are diagnosed with coronary artery disease, they should undergo additional testing to look for the presence of bifurcation lesions.

A bifurcation lesion can only be identified via diagnostic imaging, primarily computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) and invasive coronary angiography (ICA). While ICA is effective in diagnosing coronary artery disease, it has limitations when used for identifying the size and extent of bifurcation lesions, as only the lumen and not the plaque accumulations within can be visualized.

Research indicates that since 64-slice CTCA provides three-dimensional imaging, it is one of the most accurate diagnostic tools, particularly for complex bifurcations, and so should be the primary tool used for identifying bifurcation lesions.6

Diagnostic Workup

If bifurcation lesions are present, they can then be classified to determine the best possible treatment option for the patient; the most commonly used is the Medina classification of bifurcation lesions.1

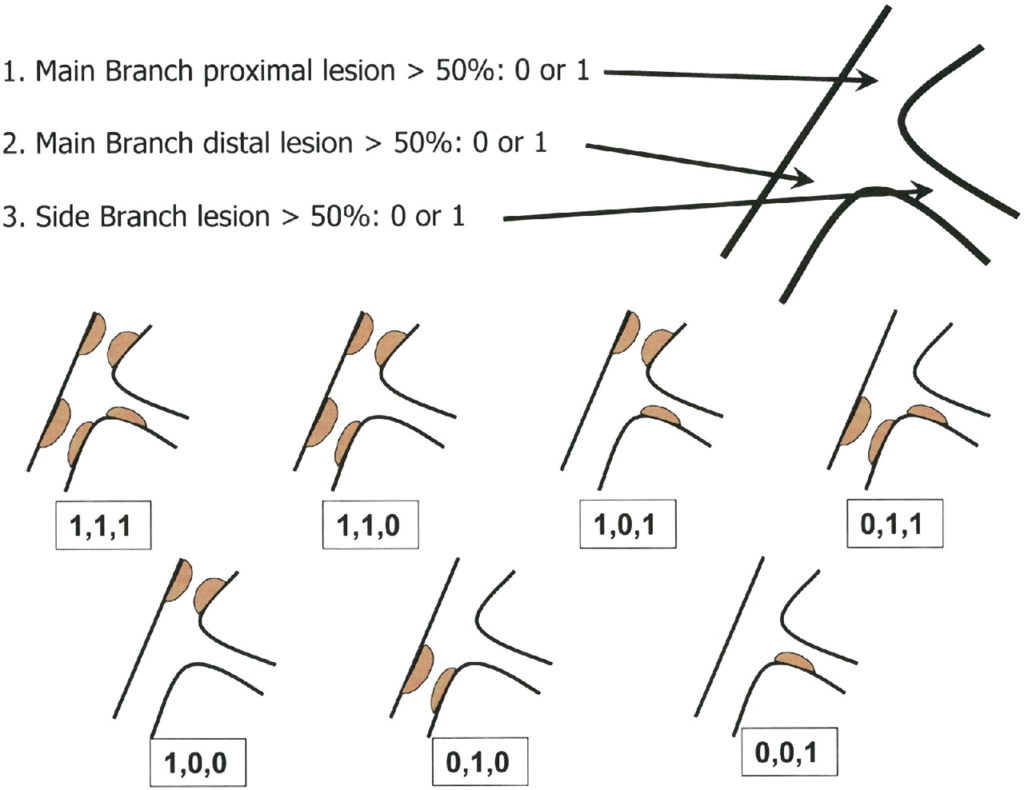

The Medina bifurcation lesion classification is popular for its simplicity compared to other classification methods, as a binary number (0 or 1) is assigned to the proximal, distal, and side branches based on the absence or presence of a stenosis.

In terms of frequency, research has found that Medina subtypes 1.1.1 and 1.1.0 are the most prevalent. Patients with either Medina 1.1.1 or Medina 0.0.1 should be more closely monitored as these classification subtypes generally have worse outcomes and a higher risk of failure after one year.7

Bifurcation Lesion Differential Diagnosis

Coronary artery disease, including bifurcation lesions, can appear similar to a wide range of other health issues. Initial complaints of chest discomfort can include the following differential diagnoses:

- Pericarditis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Myocarditis

- Pneumonia

- Pericardial effusion

- Prinzmetal angina

- Pleuritis

- Pleural effusion

To determine the exact cause of a patient’s discomfort, a thorough medical history should be taken, along with a physical exam and diagnostic testing.8

Management (Nonpharmacotherapy and Pharmacotherapy)

In the past, a range of interventions has been used for bifurcation lesions, including balloon angioplasty and bare-metal stents. But today, provisional side branch stenting is considered to be the default treatment option for the majority of cases.

Drug-eluting stenting is most often used, which contains drugs to reduce tissue growth, keeping the artery from re-narrowing. Either one or two stents can be placed. A second stent is used when the side branch is greater than 2.5 mm with greater than 50% stenosis.3

During the stenting procedure, the main vessel should be treated first. Side branches should then be treated if they meet the following classifications:

- Major flow limitation

- A large myocardial territory

- Difficult side branch access

Compared to bare-metal stenting, drug-eluting stenting results in a lower mortality rate and a lower risk of recurrence. These stents are also shown to reduce repeat revascularization and restenosis rates.9

Monitoring Side Effects, Adverse Events, and Drug-Drug Interactions

All patients should be carefully monitored during and after treatment. Because stenting involves inserting foreign material into the body, patients can be at risk for developing stent thrombosis when a blood clot forms within the stent. This can occur months or even years after the stent has been inserted; however, newer stent technology has reduced this risk compared to first-generation stents.

To reduce the risk of developing stent thrombosis, patients can be given anti-clotting medicine (dual antiplatelet therapy) after a review of the patient’s other medications to avoid any adverse drug reactions. Completion of the therapeutic course is crucial for preventing side effects, so patients should be reminded to finish the complete course of medication, as well as given guidelines on the importance of dietary and exercise changes, if needed. Monitor patients for side effects and instruct them to seek medical assistance if they experience any of the following:

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea or vomiting

- Headaches

- Rash

- Bleeding or frequent bruising10

In rare cases, other complications relating to stents can include11:

- Failure of stent deployment (occurs primarily with first-generation stents)

- Infection

- Coronary aneurysm

All patients and their primary care providers should be given a copy of the ongoing recovery plan.

References

1. Louvard Y, Medina A. Definitions and classifications of bifurcation lesions and treatment. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(suppl V:V23-26). doi:10.4244/EIJV11SVA5

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death. Updated September 6, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022.

3. Sawaya FJ, Lefèvre T, Chevalier B, et al. Contemporary approach to coronary bifurcation lesion treatment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(18):1861-78.

4. Raphael CE, O’Kane PD. Contemporary approaches to bifurcation stenting. JRMS Cardiovas Dis. 2021. doi:10.1177/2048004021992190

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD).Updated July 19, 2021. Accessed September 16, 2022.

6. Van Mieghem CAG, Thury A, Meijboom WB, et al. Detection and characterization of coronary bifurcation lesions with 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(16):1968-76.

7. Mohamed MO, Lamellas P, Roguin A, et al. Clinical outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation lesions according to Medina Classification. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(17):e025459.

8. Shahjehan RD, Bhutta BS. Coronary artery disease. StatPearls Publishing. Updated February 9, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022.

9. Généreux P, Mehran R. Are drug-eluting stents safe in the long term? CMAJ. 2009;180(20):154-5.

10. Yelamanchili VS, Hajouli S. Coronary artery stents. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 11, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022.

11. Maisel W, Laskey W. Cardiology patient page. Drug-eluting stents. Circulation. 2007;115(17):e426-e427.

Katie Dundas is American freelance medical writer and travel blogger based in Sydney, Australia.